Taking a Meaningful Pause: A Review of Memoir:

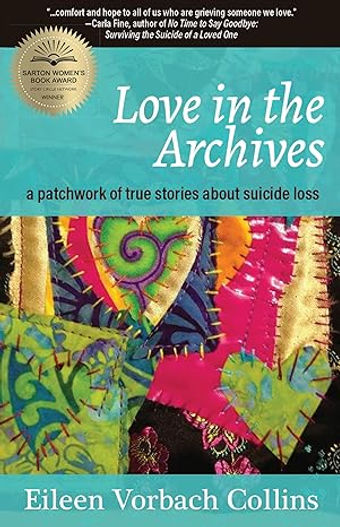

Love in The Archives: a patchwork of true stories about suicide loss

by Eileen Vorbach Collins

Ching Ching Tan

Ching Ching Tan, originally from Southern China, began her American journey with ESL at community colleges. Now a Communication Studies professor at SJSU, she's working on her memoir. Her writings, featured in New England Review, CNN, HuffPost, and others, with "How Do I Explain Myself" nominated 2023 Pushcart Prize from New England Review.

Love in The Archives: a patchwork of true stories about suicide loss

Apprentice House Press, 2023; 227 pp.; $17.66 (Paperback)

When a book makes you pause to contemplate life's profound questions, you know the author has achieved something extraordinary.

It was August 2023, just before the school year began, I was at the airport with my sixteen-year-old niece, about to embark on her first solo flight. Having promised my brother that I'd accompany her to the gate to ease his worry, we sat side by side, her shoulder touching mine, as she scrolled through Instagram, sharing memes and occasionally giggling at funny videos. In a moment of casual interest, she asked, "What are you reading?"

I had been there when she was born and witnessed every step of her growth. Now, as she entered her senior year of high school, our conversations revolved around college applications, her college essay, about what’s next.

Being an early reader I was absorbed by my Kindle reading Eileen Vorbach Collins, a debut author, and her soon-to-be published memoir Love in The Archives: a patchwork of true stories about suicide loss. Lydia who died by suicide at age fifteen, a year younger than my niece, was the reason for this heart-shattering book. Reading the title chapter “Love in the Archives,” which was the recipient of 2020 Diana Woods Memorial Award, I was pulled into Lydia’s world –her art, her collection, her room– through her mother’s soul-crushing recount after her death. “They told her she was good at art.” My niece too was good at art. At that moment, I felt like I was touching both of them. Awashed by a melancholy I could not shake, I briefly answered my niece the simple who, what age, and how. She said, “oh,” and looked back at her phone.

In one of the stories “Nag Champa 2021,” Eileen visited the cemetery thinking of herself being a cultural tourist, imagining Lydia being in a foreign country,

I am just pretending now though, to be a tourist here. Pretending it’s not really you buried under that bronze marker. That the Writer, Artist, Supernova of you is safely hitchhiking around Europe or learning another language in Asia or studying primates in Africa. Or even being a diplomat or a journalist in a war-torn country so I could worry about you properly. Worry about your safety.

I can’t move past this sentence: “so I could worry about you properly. Worry about your safety.”

Once I sent my niece away, at home, my son, who’s a year younger than Lydia, was entering high school in a few days. My mind, full of excitement and anxiety, all related to a promised future.

I closed the Kindle. My niece might not see a drop of tear in the corner of my eye.

Over the next few months, I busied myself with everything else, to get on with my life, so to speak. I didn’t open the book until two weeks before this book review was due. All writers procrastinate.

But this is a procrastination of a different kind. Something dizzying about the youth surrounding me, their vibrancy and hope, gives me a pause. I chose mundane over heartache.

How much do we have to “set aside” in order to get on with our life every single day? To Eileen, this isn’t an option. Eileen’s writing delivers the kind of precision, a piercing quality, that has the ability to translate her heartache straight from hers to yours. I wonder if it’s because the book took Eileen twenty-three years to write that gives such a distilled quality to her words.

“It softens you, a loss like that. Turns you inside-out. Lays bare your organs and makes your heart vulnerable to rupture and your nerves exposed like downed power lines in the wake of the storm. Small hurts that once bounced off your skin now linger with the excruciating agony of a piece of sand in your eye until, oyster-like, you pour your essence over it to smooth the jagged edges.”

How do you bear such pain?

First time I read Eileen, I was with the Reed Magazine editorial team going through numerous nonfiction submissions. Her “Two Tablespoons of Tim” was so raw it tore us all open. We cried alone, we cried together in the editorial meetings. In her devastatingly beautiful prose throughout the piece, she deciphers what it means to lose a daughter, all the while managing to make us laugh. “Two Tablespoons of Tim” won Gabriele Rico Challenge for Nonfiction in 2019, and it is among the myriad essays in the book where, amidst the profound sadness of her narrative, humor still emerges. Laughter intertwines with tears. Since then, I've continued to follow Eileen’s work, eagerly delving into each new publication. The pieces, as she says, have converged to shape this remarkable book.

No doubt that Eileen is a master of words, and no doubt there is such a thing as heart to heart communication, but only if you allow it. The reality is, increasingly, we permit heartache only in fiction, within the confines of a movie theater, in a designated space and time with its safety parameters. Here, we pour out our emotions, only to swiftly return to our daily business.

Even Eileen wanted that. In her Preface she says,

I wrote the story, “Roll Over,” in third person with pseudonyms. It just happened that way. Perhaps I was trying to pretend it was all fiction - that these things had happened to someone else. Another family.

On one or more occasions Collins writes about people’s apprehension, people who don’t know how to deal with the bereaved, and ask “why can’t you just get over it?”

My procrastination, looked so much like an avoidance, is it similar to Collin’s Medicare Wellness doctor, who suggested her a pill for depression until reminded the loss of her daughter to suicide? The doctor could not meet Eileen’s gaze. This story “Laughing Lesson” is one of my favorite essays in the book: “The doctor moves on to talk about my BMI, Tells me I could stand to lose a few pounds and with this, I agree. Unfortunately, he doesn’t offer a pill for that.”

Avoiding tragedy, I dare say, is a tragedy in itself.

Holding Collin’s “Love in Archives” against my chest, I wonder to the world: can reading this book turn us into feeling something beyond sympathy? Collin's work not only wraps a soothing balm around the wounds, crucial for those enduring such unbearable pain, but also, significantly to me, and hopefully to us all, it serves to recognize a mindset that seeks quick solutions, dulling our senses to instant fixes or, even worse, leading us into numbness through habitual escapes.

It’s harder to worry properly today. I think of the Israel-Gaza crisis, those who have joined Eileen’s bereaved club, and those who may join at any given moment, proper worry seems elusive. But this is our usual mode of operation - brushing over the impact of life-altering events by convincing ourselves it happens all the time and it only happens to someone else. There are too many reasons to live life as a zombie. Many of us do. Each human life has stories as rich and full as ours, and none should fade into obscurity.

The biggest human tragedy is when a life, once lived, is reduced to a statistic, labeled as suicide victims or war victims, then discussed as a public term presenting as numbers or some quick when, where, what basis, a mere chess piece in a game. Even on our own soil, what constitutes a proper worry when gun violence can randomly claim our children, or any citizen? What, indeed, is the proper worry?

The thing is, Eileen wrote this book in pieces. To me it resembles her heart, also broken into pieces. What a gift we have that she intuitively understands the link between her writing and our way of processing her words. I think it’s natural for readers to pause too. If we must pause then let’s take a meaningful pause to think what makes us turn away from the heartache, what is it that we fear? I’m grateful that Eileen so precisely captured pain, delivering a gut punch to those who seek to reduce human pain to hasty fixes and statistics. While I doubt this process can make her heart whole again, but as a reader, and a friend who cares for her, I hold onto hope for Eileen.

Expect tears, but also anticipate laughter and screams. Brace yourself for a cathartic experience you might not have known existed before. After reading this book, I’ve become a different person. You may as well.